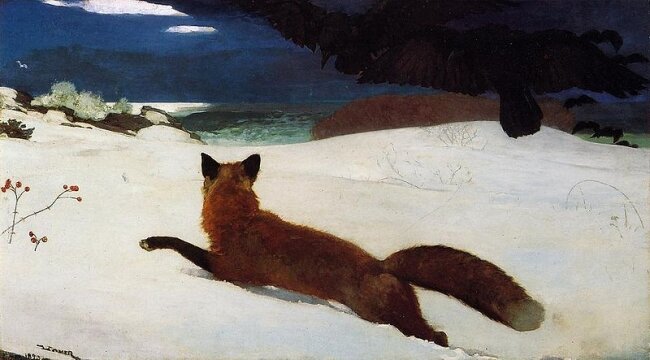

“The Fox Hunt,” oil on canvas, by Winslow Homer, 1893.

When my first wife and I

were new to each other,

we moved into a cinderblock apartment,

cozy as an eggshell, room enough

for her sewing and my novels and journals.

She kept her hands busy with needles.

I spent thick afternoons inside a book.

To improve our lives together,

we splurged our meager net worth

on a new used car—some car buff’s hobby car,

candy-apple red, lots of chrome and fancy options.

Which took us places we never dreamt we’d go.

She expected the new machine be kept clean,

something I’d scarce considered,

but consented reluctantly to wash it

that first Saturday she’d complained

of dirt and worried the sun might ruin

the car’s sugared luster.

And soon after,

expressed her dismay I’d neglected

to polish the chrome—common sense

car-care she’d learned from

her big brother’s penchant for sports cars

and cruising Main looking grand.

That very evening

I tore a hole in a sock, offered it up

to her sewing box, but later spied

my request in the garbage.

She’d be damned, she said, before she’d

darn it. Which set me back to admire

my dear old mom, who’d made a career

of mending, washing, ironing, and more.

Which I shouldn’t have spoken

aloud, as we drove with a cloud of dust

chasing after us, my bride’s teeth clenched

and needles clacking. Leather bucket seats,

separated by a mahogany console

and a bitter draft from the optional AC

pouring into the space between.

Three of us manned steaks on the grill,

boozy and a bit melancholy as late afternoon

clouds of gunmetal-blue roiled our horizon.

Through patio glass, we could hear the wives

clinking fiesta-ware, forks and spoons and knives,

their laughter boiling up from easy chatter.

We had almost nothing to say, us three, till

a voodoo mood covered the sun, chilled us

to whisper, shoulder to shoulder, youthful memories

of birds and beasts we’d shot just for the hell of it,

just for the suffering and gore. One said

he’d lie prone beside a boulder, wait for prairie dogs,

and plink them dead, one by one, as they rose

to sample daylight. Hundreds, he said. He’d swing ‘em

by the tail, sling ‘em into the weeds. Walk home

and never look back. The other grinned and said

he’d scatter-gunned dozens of magpies he’d baited

in a wire cage. And I said . . . well . . .

I don’t want to say what I said, and I’m sorry

I said it. Each of us, older now, cringed to know

how limited the pleasures our cruelties had won.

And as we sat beside our vivacious wives

—as each exclaimed how tender the meat on her plate—

we chewed and chewed. And struggled to swallow.

1 comment

Marianne Jones says:

Oct 3, 2018

Love this! He says so much through storytelling in poetry.