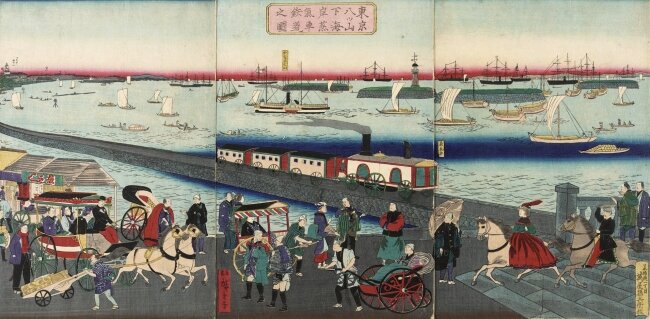

“Steam Engine Railway in Yatsuyama,” woodcut, by Utagawa Hiroshige, late 19th century.

In the morning, you rush from your home in the Tokyo area, and, as the train station comes into view, you see your fellow commuters bottlenecked back into the street in front of the station. You feel drained because you anticipate what you’ll have to undergo just to get to work. You thread your way through the crowd, and the electric bulletin board above the ticket gates confirms your conjecture: the train is temporarily out of service due to jinshin jiko, which means “corporal accident” when loosely translated, and, when accurately translated, “an accident that has caused injury or death.” This morning, with the service suspended for over half an hour, the most precise translation is that someone jumped in front of the train.

The crowd, consisting mostly of corporate workers and high school students, wait for the station staff to announce when the train will be back in service. No one complains, yet they are most likely all thinking the same thing: Why didn’t the guy kill himself someplace else?

You are unlucky this morning. Tomorrow, commuters in a different part of Tokyo may well have this bad luck. Since 1998, Japan has seen 30,000 suicides annually, according to the statistics compiled by the National Police Agency. Between April 2002 and March 2009, 2,193 people flung themselves in front of approaching trains.

Eventually, your train resumes its service. You feel depressed, even as you feel relief. Although you compete every morning for a bar or strap to hold on to, and for a tiny floor space for your feet on inside the train, the competition will be at its fiercest on a morning like this.

Nevertheless, you merge into the torrent of silently peeved commuters to jam onto the train, which is already packed with passengers from preceding stations who feel equally victimized by the self-killer. When the train stops at a station, and more passengers get in rather than get off, you hope that the other commuters on the platform will hang back and wait for the next train. But, alas, Japanese corporate workers hate to come in late for work, even when their tardiness is beyond their control. They jostle themselves into the stuffy box; now you can’t even peek through other passengers to look out the windows, though you can hear station attendants patter along the train cars and say, “Please pull back your bags!” as they shove protruding bodies of passengers to let the automatic sliding doors shut. This hassle, which station attendants undergo every morning, even without a corporal accident, is the reason why they wear white gloves. The practical-looking accessories prevent pushed passengers, including women, from harboring the impression that the hands of male attendants are directly touching their bodies. And, if the gloved hand gets caught between the doors, the attendant can just yank the hand out of the thick white cloth to let the train depart without further delay. Here in Tokyo, a one-minute delay requires the railway company to issue a voluntary apology on the train’s public-address system.

If you are a woman, you place your arms extended downwards on your torso so that your breasts won’t be pressed against whoever is in front of you. If you are a man, you grab a strap above your head. Groping is a serious offense.

Packed in like clothing and knickknacks in a tourist’s suitcase, many of the passengers hold their bags low to make what little space they can for other passengers; others keep their bags above their waists to retain what little territory they have managed to secure. If you are a woman, you place your arms extended downwards on your torso so that your breasts won’t be pressed against whoever it is in front of you. If you are a man, you hoist your bag onto the overhead rack, if there’s any room left at all, and grab a strap or bar above your head. This will keep your hands up, so that neither of your hands will accidentally slide across a woman’s back, and so that you can insist you aren’t the perpetrator should a real pervert touch a woman standing next to you. Groping is a serious offense; you’ll be detained indefinitely if you are accused of the crime. Whether or not you have committed the misdemeanor doesn’t matter. Being detained as a suspect could cost you your job and social standing, and, naturally, the well-being of your family.

Cooped up in the moving container warmed by bodies, you might perspire, but the handkerchief in your pocket seems miles away, buried under your arm, which is pinned against your neighbor’s flank. The train occasionally glides into a curve, forcing your torso to stoop in one direction and your lower body to pull in the other, a posture that is possible only when your entire body is supported by others’ in such close proximity. If you are clutching a strap above a row of seats, the centrifugal force nudges you into the space between the knees of the person sitting in front of you, making both you and the person furiously avoid each other’s eyes.

All this eases up at a major railroad junction like Shibuya, Shinjuku, or Ikebukuro, where you get off with perhaps forty to sixty percent of the other passengers to make connections or to head for your workplace on foot. As soon as the train spews the onrush of frazzled passengers onto the platform, the worst part of the journey is over. You can’t help but take a deep breath, and wonder if the suicide chose this way of dying to torment people like you, people who cluck their tongues at his death.

2 comments

says:

Sep 20, 2017

What a wonderful glimpse into a society other than my own. Ms Fujimoto’s writes eloquently about an everyday occurrence that many take for granted–the commuter train! I enjoyed this essay.

Harriet Cooper says:

Sep 20, 2017

To think I used to complain about Toronto’s subway system. Yes, it’s busy but nothing like Tokyo’s. Thank you for the glimpse into this system and for the a peek into the minds and bodies of the commuters.